Anti-vaping laws a case of smoke and mirrors

- nmcmahon21

- Jul 29, 2025

- 5 min read

Victoria has the strictest vape laws in all of Australia, yet despite the government’s efforts, e-cigarettes seem as accessible as ever. Beyoncé Kariuki investigates.

Despite some of the toughest vaping laws in the country, Victoria’s youth continue to be drawn to the enticing, addictive haze of e-cigarettes.

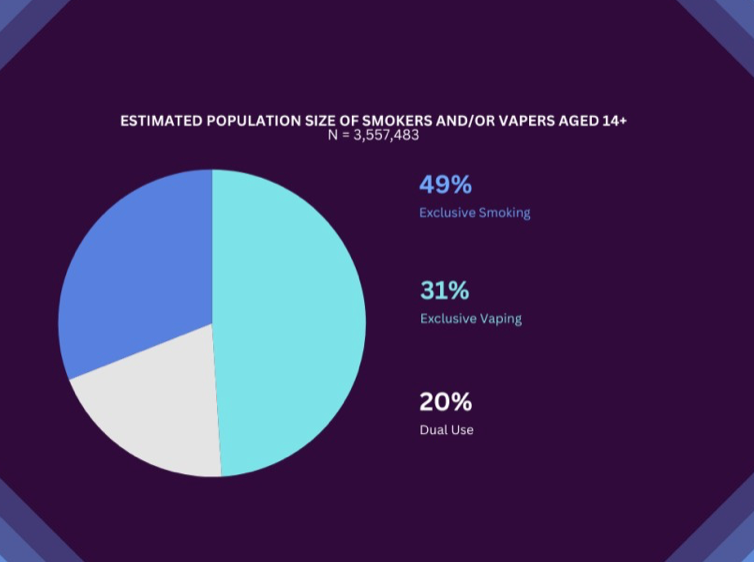

While public health campaigns, national reforms and retail crackdowns have attempted to stamp out this rapidly growing trend, the reality paints a different picture. Vaping remains deeply embedded in youth culture in Victoria. It is an epidemic that regulations alone have failed to contain. According to the National Drug Strategy Household Survey, vaping rates are increasing across Australia. In 2022–23, one in five people aged 14 and over reported using an e-cigarette at least once in their lifetime.

The Cancer Council reports that 12.9 per cent of teens aged 12–15 have vaped in the last month, and 22.1% of 16–17-year-olds have vaped in the last month. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare says the proportion of current e-cigarette users aged 14 and over increased from 2.5 per cent in 2019 to 7% in 2022–23.

Matthew Beverley-Stone, a nurse and senior lecturer at La Trobe University, says: “For young people, it’s often a combination of social influence, curiosity and targeted marketing. Vapes are marketed as sleek, harmless alternatives to smoking and, with flavours like mango or bubble gum, they’re clearly designed to appeal to youth.”

The health consequences, he says, are already beginning to show: persistent coughs, shortness of breath and early signs of lung damage. But it’s the psychological toll that remains less visible and potentially more dangerous in the long run. “Addiction is central to this issue,” Beverley-Stone says. “Nicotine is incredibly addictive, and many young people don’t realise they’re dependent until they try to quit. It becomes more than a habit; it’s a coping mechanism.”

According to the Department of Health and Aged Care, while scientists are still learning about e-cigarettes, they do not consider them safe. Even devices that do not contain nicotine can contain dangerous substances in their liquids and aerosols, including formaldehyde (used in industrial glues), acetone (nail polish remover), acetaldehyde (used in perfumes and plastics), acrolein (found in weedkiller) and heavy metals — all cancer-causing agents.

Direct health risks from vaping include mouth and airway irritation, coughing, nausea and vomiting, poisoning and seizures, nicotine dependence, respiratory problems and permanent lung damage. While e-cigarettes do not contain tar — the lung cancer-causing ingredient in cigarettes — scientists believe vaping can still increase the risk of lung disease, heart disease and cancer.

For 21-year-old Catherina Ligidakis, vaping started in high school “as something fun” and “harmless.” But it quickly spiralled into something she couldn’t control.

“I felt naked leaving the house if I didn’t have my vape. I panic if I run out or forget it at home. I am really dependent on it, but I also don’t want to stop,” she says.

Even when trying to quit, the social pull makes it nearly impossible.

“My friends all vape. My co-workers vape. It’s always around me,” she says.

“Even when I want to stop, someone starts vaping in front of me, and I start to crave it. Everyone in the stockroom vapes. It’s like a social thing. There’s even a vape store directly across from our store, and it’s clearly not legal, but they sell to anyone.”

While Victoria’s laws go further than any other state by banning even therapeutic vape access via prescription, it hasn’t stopped young people from getting their hands on them and stores openly sell vaping products illegally. In Victoria, the Tobacco Act 1987 prohibits the supply of vaping products to anyone under 18. According to the Victorian Department of Health, it is illegal for businesses such as tobacconists, vape shops and convenience stores to sell any type of vape or vaping product.

Callum Richmond, 22, doesn’t vape himself but is surrounded by it. “It’s everywhere. Hanging out at someone’s house, heading to a party, grabbing food. Someone’s always got one. It’s just become background noise,” he says.

Despite laws tightening supply, enforcement is weak. “It’s like the rules exist on paper, but not in real life,” he says.

Police from the organised crime taskforce, known as VIPER, raided a tobacco shop in Horsham, western Victoria, in February this year, seizing hundreds of illegal e-cigarettes. As recently as April 14, police caught a man selling e-cigarettes to children in another raid that uncovered hundreds of illegal products. Notably, in October 2024, police recovered more than 100,000 vapes worth approximately $8 million.

Beverley-Stone warns that strict bans, without pathways to quit, are driving the issue further underground. “We’re already seeing the emergence of a black market, where people purchase unregulated or counterfeit products. Harm reduction, not prohibition, should guide our approach,” he says.

Victoria is the only state that doesn’t keep a register of businesses selling tobacco products, despite it being recommended in 2022. A licensing scheme is due to begin on July 1 but won’t be enforced until 2026. The cost of a tobacco retail licence ranges from $1,100 to nearly $1,500. By comparison, it is $475 in Queensland and $340 in South Australia.

David Inall, CEO of the Australian Independent Grocers Association, believes the high cost of licences in Victoria may force many independent stores to stop selling tobacco. This price difference may push retailers to sell e-cigarettes unlicensed and unregulated. Furthermore, under the scheme, inspectors are not permitted to investigate illegal vape sales.

For many, vaping isn’t just a personal habit — it’s become a ritual. Breaks at work become bonding sessions over a vape. Stepping outside for a puff becomes a social event.

“It’s like our little ritual,” Ligidakis says. “If someone doesn’t vape, they’re kind of left out. That sounds ridiculous, but it’s true.”

Even Richmond admits to feeling left out. “There’s a bit of social FOMO. It’s a bonding moment, and I’m not part of it,” he says.

Beverley-Stone says: “This peer dynamic reinforces use [of vapes] and makes quitting even harder. Add stress, anxiety or unstable home environments, and the reliance deepens. We see mood instability, heightened anxiety during withdrawal periods and depressive symptoms.”

Young people are increasingly turning to vapes to cope with stress, academic pressure or boredom. But nicotine dependence only worsens mental health over time.

“Nicotine temporarily boosts dopamine, which can give users a short-lived sense of calm or focus,” Beverley-Stone explains. “But it’s a false sense of relief — it creates a cycle of dependence that worsens the very symptoms people are trying to treat.”

Ligidakis agrees. “I know it’s bad. I get out of breath now, I wake up coughing, and I feel awful. But it’s so normalised that it feels easier to keep going than to explain why I want to stop,” she says.

Campaigns like Flip the Vape and ongoing crackdowns have aimed to discourage young users, led by the Victorian Aboriginal Health Service. According to Campaign Brief, 22% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15+ have tried vaping. Quit with Pride, launched on 7 April, features across radio, posters, digital channels and within communities. The campaign highlights data showing LGBT+ people face disproportionately higher rates of smoking and vaping. The 2022 Victorian Smoking and Health Survey showed 21.7 per cent of Victorians who identify as LGBT+ smoked and 12.2% used vapes.

In the US, Chicago’s Department of Health has resorted to offering children the chance to win scholarships if they pledge to stop vaping. According to the department, more than 10,000 children have already pledged.

“The crackdowns are only partially effective because they don’t address the demand side,” says Beverley-Stone. “You can restrict access, but if you don’t help people manage addiction or provide safer pathways, the behaviour continues underground.” He believes the solution lies in education, support and harm reduction.

Ligidakis says she would consider quitting only if she had more support.

“If there were proper programs, counselling, or even if my workplace took it seriously, I’d feel less alone. Right now, it feels like I’m the only one thinking about it.”

Comments